The Negative (of) Change

Curating the Spectre of Socialism

The ultimate dream of every researcher is to come across a finding that nobody else had discovered before. One such thing happened to the writer of these lines, quite suddenly and unexpectedly. On 20 March 2019, during our regular ‘expeditions’ at “Kristal-Zaječar,” now a derelict socialist factory giant in eastern Serbia, a photographer friend and I had decided to check one of the garbage piles.

Collection “Crystal-Zaječar”, www.skvermagazin.com

The discovery in the dark shocked us: hundreds of discarded celluloid stripes of film negatives were hiding in the dirt. Treated similarly like the broken pieces of glass and crystal lying around, our immediate reaction was to bring those stripes of aborted history to safety, still not knowing exactly what they contained.

By Public Space With a Roof: Adi Hollander, Vesna Madžoski, Tamuna Chabashvili

Images: Crystal-Zaječar in SKVER collection

Sound: Claudio Baroni; Performed by Adi Hollander, Mikica Andrejić, Tamuna Chabashvili, Vesna Madžoski

As rays of light fell on them, a parallel universe opened. Hundreds of images of unfamiliar faces and unusual moments from the socialist factory came to life. In the words of Allan Sekula (Sekula 2002, 447), we were confronted “by the appearance ofhistory itself.” What was to be done?

Crystal-Zaječar, 2021. Photos by Mikica Andrejić

Before we knew it, this unusual discovery turned us into guardians, the guardians of a collection we still could not understand. Before we knew it, the collection forced us to become researchers of the socialist past, with a mission to understand what happened there: what made its previous owners to abandon it, to never turn back? We could have pretended this had nothing to do with us, we could have pretended this was ancient history. Nevertheless, if history is, in the words of Roland Barthes (Barthes 1981, 64) “the time when we were not born,” it became clear we would be lying. Being born in the times when the factory was still open, particular memories started to emerge, forcing us to admit we must have been somehow a part of the story that was now starring at us from the images. A period of our lives we thought we forgot, a period of our lives we cannot explain even to ourself. If, following Walter Benjamin (in Leslie 2015, 19) photography is “the site where evidence might be found” perhaps we could begin this analysis with the attempt of understanding what kind of evidence fell into our hands in the first place.

Crystal-Zaječar, 2021. Photo by Mikica Andrejić

The Dark Side of Photography

This archive-in-becoming consists of several hundreds of photo negatives – entities that seem able to survive the level of destruction paper-printed images cannot (the collection can be seen in a digitized form at: www.skvermagazin.com.) They have been scratched here and there, luckily not ruined by animal excrement, and had managed to survive the rough hands and feet of the ‘vandals’ that came before us: made of a sturdy enough material, they were able to survive the passing of time and energy of many.

Collection “Crystal-Zaječar”, www.skvermagazin.com

Soon, the questions about the material nature of our finding started to emerge; with it, first problems as well. Namely, although being a fundamental part in the process of developing photographs, the history and theory of photo negatives is shockingly scarce, almost non-existent. All focus and fame are for the images developed from them, obliterating the fact that the writing of light of photography happens on the negatives. In the words of Geoffrey Batchen (Batchen 2020), the author of a rare study on the topic, “negatives are truly the repressed, dark side of photography.” As Batchen (ibid.) points out, Sir John Frederick William Herschel (1792-1871), a scientist and experimental photographer who ‘baptized’ the negatives, insisted on “dividing photography into two… even when they are physically identical. And the very language used to make that division, negative and positive, is rhetorically infused with prejudice. The distinction between them therefore comes with a disparity in value; it represents a political as well as a technical hierarchy.” This system of designation also had a racial component as well, since, in a photographic negative, “fair women are transformed into negresses” (ibid.). The implications of this were implanted into photography from its early days, forever changing the manner in which the negatives were to be perceived.

Unfairly, we seem to see the negatives, as Batchen (ibid.) has defined them as “utilitarian tools, redolent with potential, remaining incomplete entities” while photographs are “assumed to be entirely whole and complete, an end product in and of themselves. We treat those prints as images rather than objects.” Inviting an inversion of our usual perception, the negatives seem to testify about the failure of our optical apparatus: not being trained to see them as images, we prefer to discard them and focus on their printed versions instead. If one pays close attention, one might notice that photographs are made by series of adjustments, manipulations and interventions in the dark room. Nevertheless, we continue to fail to see photographs as objects to be regarded under permanent suspicion, confusing them for the things depicted in them.

In this, one could perhaps identify one of the founding fears of modernity, that of fear of proliferation, as Michel Foucault (1998) defined it, or the fear of the instability of images and meanings produced from the negatives. We are to pretend there is only one stable version of an image that can be reproduced, when the truth is far from it. In Batchen’s words (ibid.), “the negative, it turns out, is a site where all these opposing forces are held in a state of irresolution, where every potential outcome is available but none is assured. No wonder, then, that the negative is so often seen as photography’s most dangerous element, the element to be feared, controlled, and, if possible, suppressed.”

If we were to follow Karl Marx or Walter Benjamin in our analysis, a particular parallel becomes evident: the prioritization of photographs to negatives points at the essence of capitalist ideology of concealing the origin of things, as well as their means of production: by obscuring the means of its production, the ultimate fetish of photographs was created.

Batchen (ibid.) further argues that the ideology that represses negatives in the history of photography is a direct consequence of the particular type of economy this new medium had introduced: “They are, after all, an unwelcome reminder of the act of reproduction. They speak of photography’s lack of singularity, of its capacity for multiple copies and therefore for multiple authorships and divided ownership.” Even more, “authorship has always been a complicated matter when it comes to the making of photographs. And this is especially so because of the collaborative nature of the medium itself.” The topic of authorship and ownership over the rights to reproduce images is a discussion that is still ongoing. As we can see, one of the consequences of finding those negatives was an interruption of our usual photoshoots of factory ruins, forcing us to stop being ‘educated tourists’ in our own town, and turning us into the archaeologists of the present. Hence, who was their author? Equally important, who was their owner?

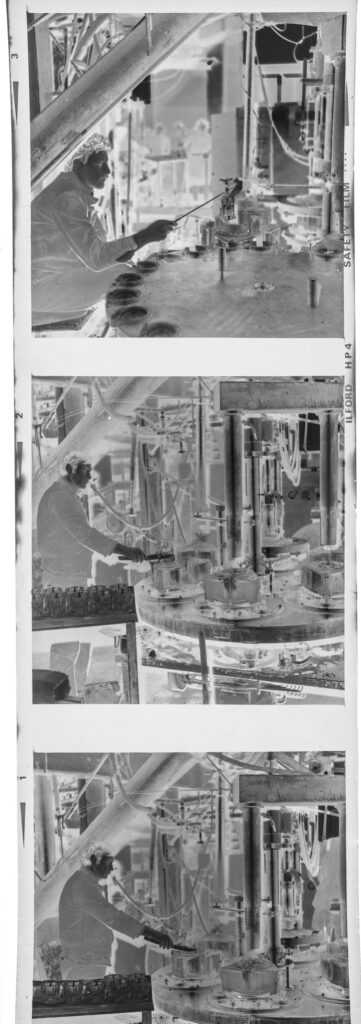

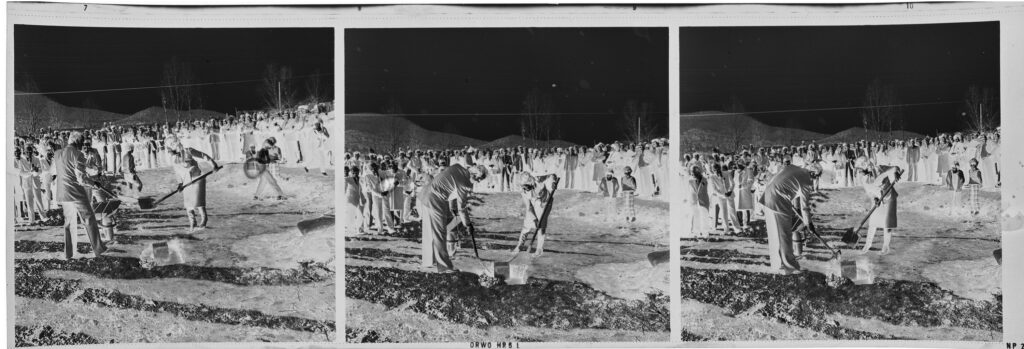

Proletarians of Creation

By finding the stripes of negatives instead of a selection of printed photographs, we gained access to the series of images that would normally be considered as failed. One could even say that they show a series of attempts to capture something, from a perfect portrait of a worker to the promotional images of glass items produced. What they offered us was a rare entrance into the world of production that normally stays hidden for everyone outside the factory gates. Black and white images of men blowing glass, women engraving the crystal, cooks posing for their portraits, visits of important people, images of new trucks, workers’ meetings and protests, celebrations and anniversaries, piles of chemical material needed for production, football and handball matches, boxing competitions, travels and excursions. Images with the flash turned on or mistakenly off, bad and crooked frames, upside-down images: all to be fixed in the dark chamber.

What became clear is that these images were made by someone ‘on the inside’: we learned that most socialist factories used to have their own in-house photographer, also considered a staff member, being there for various tasks that had to do with images, from capturing important moments to producing promotional material. Nevertheless, we encountered an obstacle while trying to identify the single author behind these images. In the interviews with former workers, we found out some names and nicknames, but it soon became clear that there were several ‘proletarians of creation’ (Bernard Edelman in Sekula, 444) who had passed through the factory in its long history. This further made it impossible to identify individual authorship of particular negatives, a fact that seems to underline the problem this new media had created from the beginning. In the words of Esther Leslie (29), “photography is an art of replication, not one of private possession.”

What were the actual means of production behind these images? As previously noticed by many, the meaning of the images depends on their context. Or, as Sekula (445) put it, “Despite the powerful impression of reality (imparted by the mechanical registration of a moment of reflected light according to the rules of normal perspective), photographs, in themselves, are fragmentary and incomplete utterances. Meaning is always directed by layout, captions, text, and site and mode of presentation.”

Collection “Crystal-Zaječar”, www.skvermagazin.com

The search for the answer to the context that produced them brought us to the library archive and the discovery of factory newspapers. Soon, many faces gained their names and puzzling events suddenly became deciphered. There was no doubt that the majority of the images featured in the newspaper came from the negatives in ‘our’ archive, being only a minor selection of images we were now able to reproduce.

We further learned that factory newspapers were a usual practice in the majority of factories in socialist Yugoslavia. Furthermore, they were considered one of the pillars of workers’ self-management on which all production was based. By placing photographers in the midst of the production process, perhaps we can find an example of the belief in true political commitment of a once separate creative class. In Walter Benjamin’s words (1934), “political commitment, however revolutionary it may seem, functions in a counter-revolutionary way so long as the writer experiences his solidarity with the proletariat only in the mind and not as a producer.”

On the other hand, Sekula (448) argues that if an event has been pictured, it is given a particular significance, and in turn “history takes on the character of spectacle.” The danger of this process is that by looking at the spectacularized images of the past, one might be caught in an experience that “veers between nostalgia, horror, and an overriding sense of the exoticism of the past, of its irretrievable otherness for the viewer in the present” (loc. cit.), an experience we would most likely have had if we were to rely only on the images from the factory newspaper. Nevertheless, this narrative became severely disturbed by the discovery of the negatives, a series of ‘failed’ images that fought their way to become an equal registration of the past. The only danger, Sekula warns us, is in turning those images into aesthetic objects, as “the very removal of these photographs from their initial contexts invites aestheticism” (loc. cit.).

Fall Between the Cracks

The thing that surprised us most at the place of production of the found negatives, the crystal factory, was that there were still thousands of produced objects left around thirty years after its closing. Due to negligence or another similar reason, almost everything was broken, and with it any hope of those objects being sold at the newly established capitalist market. The factory was privatized at the turn of the century, automatically turning collectively owned tools and means of production into private property. The former workers were laid off and forced to seek employment elsewhere, left with a ruin in place of a factory: a ruin nobody wanted anything to do with anymore.

Among the found negatives, there were dozens depicting crystal objects that were once mass-produced here. Believing that capitalist mass-produced consumerism was something rejected by communism, the next question that inevitably came to our minds was what, then, the difference was between mass-produced objects in these two opposing systems. The possible answer was found in one of the articles in the local newspaper, explaining the ideology behind the decision to produce crystal. Namely, the aim was to make those once upper-class objects available to everyone. As it seems, the crystal glass was to be seen just as a glass made of crystal. The aura of the fetish was erased.

The incredible amount of broken crystal objects we had encountered appear to be stuck between the cracks of the two systems, communism and capitalism, waiting to be assigned a new value or turned into matter again. Together with it, the negatives got stuck in the exact same crack. Crystal is usually considered to be an almost unbreakable material, nevertheless it is the material nature of the negatives that had managed to surpass even this. While it became impossible to reconstruct the objects from the broken pieces, the images of the past remained intact.

The scandal of the found images, following Barthes (82), was in the fact “that what I see has indeed existed.” We were forced to see the resurrection of happy workers, persevering in the experiment of self-management, living in a system far from perfect but seemingly able to provide for all their needs. Images that, although black and white, seem to contain much more colour than the bleak reality of present-day workers’ rights: all this making it almost impossible to explain how a world like that was abandoned.

All we can do is look at those images, waiting for the Benjaminian “sudden moments of clarification or illumination” (Cadava 2001, 49) read from the shattered pieces. In order to be able to read them, we cannot act as innocent bystanders of history: the us in the present should recognize the apparition of ourself in the images of the past as we were once its dream. In order to understand past experience, one must take into account the necessity of a distance, due to the fact that “we experience an event indirectly, through our mediated and defensive reaction to it. For Benjamin, what characterizes experience in general, experience understood in its strict sense as the traversal of a danger, the passage through a peril – is that it retains no trace of itself: experience experiences itself as the vertigo of memory, as an experience whereby what is experienced is not experienced.” (50)

By Public Space With a Roof: Adi Hollander, Vesna Madžoski, Tamuna Chabashvili

Images: Crystal-Zaječar in SKVER collection

Sound: Claudio Baroni; Performed by Adi Hollander, Mikica Andrejić, Tamuna Chabashvili, Vesna Madžoski

Eduardo Cadava links this to the Freudian understanding of trauma and his insistence on the distance between a traumatic event and our experience of it: “Confronted by an event that paralyzes us by the magnitude of its demand, an event that we recognize as a danger, we fend off the danger through the process of repression: the danger is in some way inhibited, and its precipitating cause – in this instance, the blitz itself – is forgotten.” (51) Nevertheless, this period of latency, the forgetting that attends the experience of shock, is something we must take into account when thinking about the past.

In a similar manner, the photographic effect “arrests time and experience,” evoking “a devastation that destroys our ability to refer to it.” (52) If one was to be Benjaminian historical materialist, one must focus on the hidden within the image, this way rejecting the idea of history as a mere reproduction of the past: “Effecting a certain spacing of time, the photograph gives way to an occurrence: the emergence of history as an image.” (53) History does not come to us voluntarily. Rather, as suggested by Benjamin (55) “history in the strict sense is an image from involuntary memory, an image which suddenly occurs to the subject of history in the moment of danger.”

In Benjamin, we find a rare inclusion of negatives into the theory of photography, defined as an element which links history to images: it is only in the future that the possibility of interpreting the past can be realized. The question of future brings us back to the question of the archive. The archive’s “breakdown of memory is to say that it begins with forgetfulness, with an amnesia that ruins its commemorative principle.” (57) The past cannot be recovered, but the trauma of its loss continues to live on in various forms. All we can do is learn to read the past. Following Sekula (ibid., 445), the archive should be seen as a “tool-shed, a dormant archive,” where “meaning exists in a state that is both residual and potential” and where past uses coexist “with a plenitude of possibilities.”

As we have learned, the archive of negatives we were forced to create brought to the surface the inherent binary structure of photography in which each part depends from the other, “such a structure means that the photograph is neither singular nor static but is instead always in a state of becoming, always in the process of differing from itself, always in motion. Any history that arrests this motion by confining itself to a procession of single photographic prints… also reproduces the politics of privilege that Derrida has identified. It privileges, in other words, white over black, male over female, original over copy, singularity over multiplicity, simplicity over complexity, illusion over truth.” (Batchen, ibid.)

Crystal-Zaječar, 2021. Photo by Mikica Andrejić

In the silent cohabitation with the ruins of their past lives, we might see the signs of the repression of a trauma of loss experienced by the once socialist workers, patiently hoping to understand it sometime in the future. Under the guise of democracy, a completely opposite system of production of reality was installed as well, one heavily dependent on the constant production of images.

Nevertheless, in their ability to weave into people’s lives and begin to change them, Benjamin saw the “revolutionary use-value” of images, with a role to play “in further social unravelling and reconstruction.” (Leslie, ibid., 30). When it comes to the images of socialism we were forced to see, we might close this discussion with the horrifying effect every photograph has, that coming from its link to resurrection. In Barthes words, “and the person or thing photographed is the target, the referent, a kind of little simulacrum, any eidolon emitted by the object, which I should like to call the Spectrum of the Photograph, because this word retains, through its root, a relation to “spectacle” and adds to it that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead” (9). Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were right to claim in their Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848) that a spectre of communism haunts Europe. Almost two centuries later, we might offer an addition: a spectre is indeed haunting Europe – it is the spectre of communism in images.

Crystal-Zaječar, 2021. Photo by Mikica Andrejić

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida, New York: Hill and Wang.

Batchen, Geoffrey. 2020. Negative/Positive, London, New York: Routledge, e-book.

Benjamin, Walter. 1934. The Author as Producer, https://theoria.art-zoo.com/the-author-as-producer-walter-benjamin/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

Burgin, Victor. 1982. Photographic Practice and Art Theory, in: Thinking Photography, V. Burgin, ed., Hampshire and London: Macmillan Education, 39-83.

Cadava, Eduardo. 2001.Lapsus Imaginis: The image in ruin, in: October, vol. 96, Spring, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 35-60.

Derrida, Jacques. 1995. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, in: Diacritics 25.2, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 9-63.

Foucault, Michel. 1998. What is an Author, in: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, J.D. Faubion ed., New York: The New Press, 205-222.

Leslie, Esther. 2015. Introduction: Walter Benjamin and the Birth of Photography, in: On Photography, W. Benjamin, London: Reaktion Books, 7-58.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Friedrich. 1848. Manifesto of the Communist Party, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf(accessed on 1 December 2022)

Sekula, Allan. 2002. Reading an Archive: Photography Between Labour and Capital, in: The Photography Reader, L. Wells, ed., London, New York: Routledge, 443-452.