The Absence of Things We Take for Granted

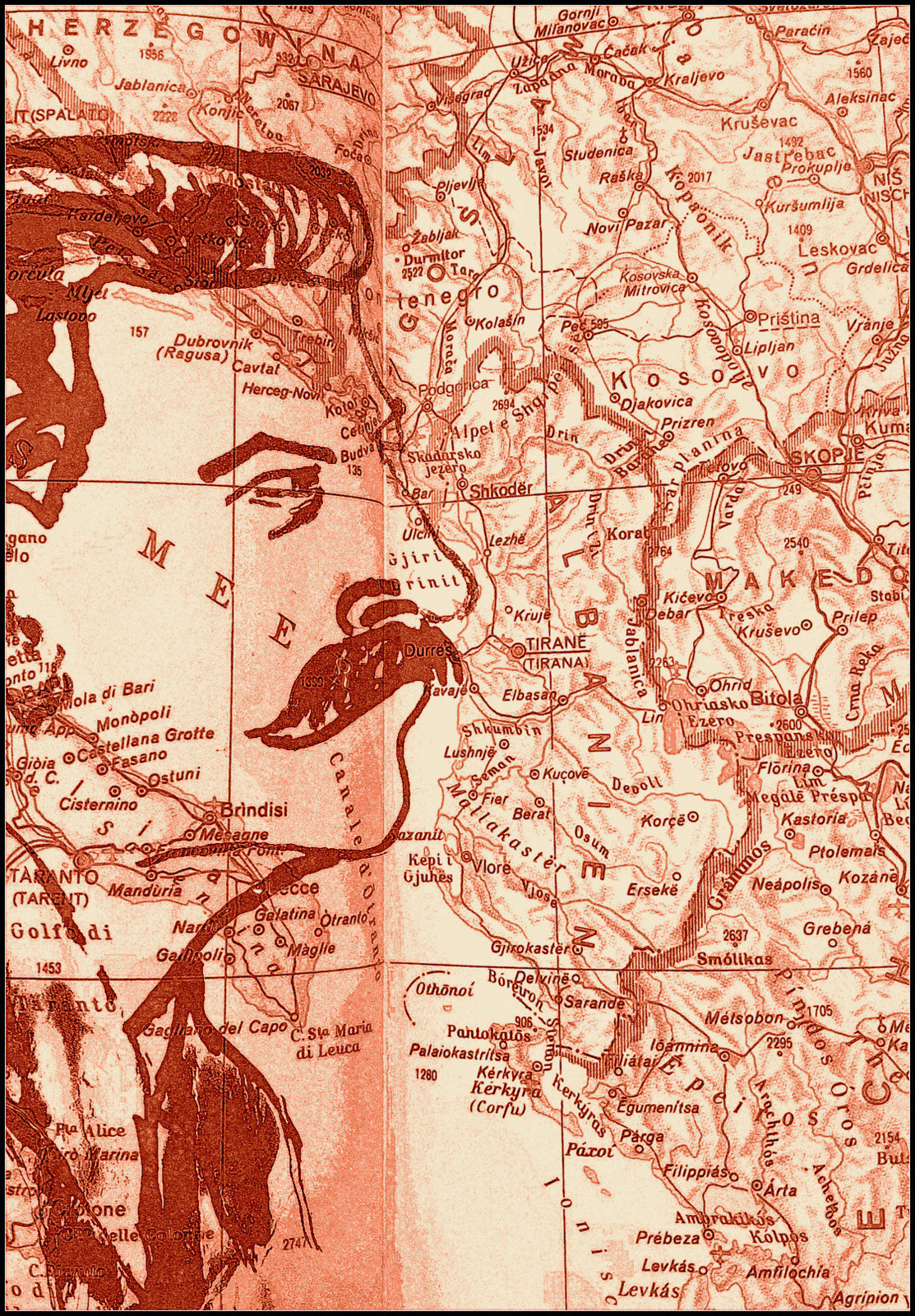

Albania’s Prison Literature

Upon my first post-Corona-lockdown visit to Albania, I was delighted to get to know a number of young Albanian adults who were interested in arts, architecture and the like. They shared a critical view of the present state of the country, but unlike the older generation, they also maintained a curiosity and were eager to do something about the situation, rather than to seclude themselves into resentful complaining. Together, we decided to pay a visit to Spaç, the notorious former prison camp in the northeast of the country. We were all aware that the site should be turned into a memorial instead of being left to decay, as we discovered it to be. Still I was astonished to find out that the young intellectuals from Tirana had no knowledge about the conditions in Spaç under the dictatorship. Of course the few signs that were put up there giving some information on the camp were not a big help.

On the other hand, I was somehow able to reconstruct the place in my mind, for I had read numerous accounts of former politically persecuted who had been detained at Spaç. They have described their years of humiliation and forced labor, which still is the main source of information about the time in question. Even though the Spaç we visited in 2021 might as well have been an abandoned school building, I mentally rebuilt the prison, thinking for instance about how the dorms had been described by the witnesses, the four-story beds, and so on. This shows us that a book often can teach us more than travelling around the world. It shows us the importance of the Albanian prison literature, especially since the state often fails to promote a culture of remembrance, in spite of civic attempts to turn the former prisons into museums.

In fact there are some museums about the dictatorship now, mostly in Tirana, but one is inclined to think that they are meant more for tourists rather than for the Albanians themselves. It’s the prisons, located in non-touristic spots, that represent an obligation towards the former victims of Enver Hoxha’s regime. Tragically, when we constate an absence of memory here, we come back to a characteristic attribute of life in prison: the absence of things we take for granted. Prison literature is one of the few means by which victims can find their voice. Their accounts make the absent visible. What was absent back then?

Of course, incarceration always goes along with the absence of LIBERTY. That applies especially to a totalitarian state like Albania has been, because second sentences were daily fare, and even upon their release, prisoners were isolated in society, marginalized in a country that actually can be seen as one big prison at that time. What else was absent?

We are familiar with the Stalinist practice of twisting the TRUTH, which George Orwell has masterly depicted in his dystopic novels. In his book Second Sentence. Inside the Albanian Gulag, both a prison narrative and an analysis of totalitarian structures, Fatos Lubonja describes how conspiracy theories were designed to keep the persecuted in prison. Prisoners are forced to confess to absurd, made-up military attacks from abroad, intended to overthrow the “power of the people” (2009 47f, cf. also 52ff). By the help of the ambiguously formulated paragraph 55 that dealt with “agitation and propaganda”, anyone could become a suspect at any time.

This means there can hardly be TRUST. There are spies and informers everywhere (ibid. 23f). Even your fellow inmate can be one. This goes along with the lack of FRIENDSHIP. In his autobiographical work Spaç, Maks Velo writes:

“One reason for not making friends was that the people who were close to you changed frequently because of the way the work was organized. Every month new formations were made, work brigades were reassembled and in the living quarters changes were made accordingly, so that each brigade would be together in one room. […] Having to move from one room to another was another burden for the convicts. As soon as we got used to a place to sleep and the inmates near us, we had to go and start all over again.” (2010a, 167f)

The constructed image of the enemy is a pillar of the regime. Velo recalls:

We are the enemies. I remember how, after my arrest, the investigator made me sign the order of my arrest, gave me a whack, and called me: ENEMY. And to this very day, I haven’t been able to understand whose enemy I am. […] How many times was this declared at party congresses. “Enemies of the People.” This was our title. As if you had the title “Artist of the People” or “Educator of the People.”

We deserved this title by virtue of our countless sufferings, and we don’t relinquish it. It was said to no purpose that we were the Enemies of the People, we were their enemies and the enemies of communism. That was the truth (cited in Segel 2012, 45ff).

Politically persecuted Lekë Frroku was hardly able to exchange a word with anyone outside: “I can even say that all the friends I had were in prison; I didn’t have any friends outside.” Outside of the prison walls there are neither “friends” nor “comrades”, only the fellow sufferers and inmates remain, with whom one can communicate (Kienzle 2023, 168).

One example for the absence of LIGHT is the gallery in Spaç, where the forced labor is carried out. In detail, Velo describes the horror of the tunnel, according to him one of the strongest means of pressure of the Albanian State Security (Sigurimi) to recruit spies or false witnesses.

“When I entered this mushy, damp, muddy, propelling darkness with its inconsistent form, at times compressed and at times with cracks of light, with its ceiling right over your head, with those crooked tunnel beams, broken, cracked from the pressure, I realized I had a mountain above my head which rested there merely by sympathy, because those pitiful constructions surely wouldn’t hold it.

It was a darkness that smashed into your face like a piece of mud, and took your breath away, sour and sneaky.” (Velo 2010a, 211)

Regardless of the uniform prison COLORS, Maks Velo lets down a true cascade of colors during his pre-trial detention. They evoke life in freedom:

“The yellow of the egg, lemon, chamomile, sunflower, corn, apricot, orange, azure blue, coffee grounds, walnut brown, the grey of the water ouzel, canary colors, earth colors, wheat colors, hedge rose, cherry red, chestnut colors, pea green, carrot, eggplant, rowan, tuff stone, pitch black, apple green, goat cheese, ash grey, milky white, wolf’s milk, onion colors, dark blue, coal black, dapple, speckled, mouse-gray, fox-red, rust-colored, brick-colored, leek-green, silvery, the color of quinces, pomegranate-red, olive-green, lilac, violet…

A collection of names, designations and expressions for colors suddenly came to my mind.

They had been abducted by the air, the sky, the woods, the fields and placed in the popular palette of colors. They appeared in front of me at the cell wall, like living spots that began to move and mingle. After all the months of prison grey that created black crimes, I saw transparent, flying colors flooding my room.

All the colors of the homespun stockings, bags, aprons, scarves and carpets that I had collected and hung up in my studio, I now saw clear, bright and pure in front of me.

I knew the colors would never leave me. And just when I thought I’d lost them forever, they brought me happiness.” (Velo 2010b, 14f)

This is not untypical of prison writing. In her work on Gulag literature, Renate Lachmann (2019, 236) notes that the naming and enumeration of colors appears frequently and suggests a receptivity that turns away from the muddy grey of the camp. A rescue from the actually existing narrowness can be achieved through an artistic visualization carried by the protagonist in his or her spiritual hand luggage. This process is an act of total solitude; it cannot be shared with anyone. It is a meditative exercise that keeps the narrator from decay. This inner serenity, the feeling that everything can, but nothing has to be done leads to peace of mind and contentment. The lack of freedom of movement is thus compensated by the power of imagination and thinking.

There seem to be no SEASONS. Especially in Spaç, there is either “scorching sun” or “winter frosts” (Lubonja 2009, 3, cf. also 28). Ultimately, there is the absence of SPACE, which may appear to be the most dreadful aspect. In his prologue “The Caged Wolf”, Lubonja notes: “We had all assembled and were standing packed against one another, in ‘the field’ as we called it, an open space far too small to hold us all comfortably.” (2009, 13) (I have written more thoroughly on this aspect in my study on Space in Albanian Literature; Kienzle 2023)

In Albania, there have been numerous individual initiatives to remember the past, the dictatorship, and the prison. Witnesses have written about their experiences in various forms, through poetry, autobiographical accounts, prose sketches, etc. What has been translated into English so far? Former Spaç inmate Fatos LUBONJA (born 1951) is probably the most active and most prominent writer and public figure struggling for memory culture and public awareness. His volumes Second Sentence (“Ridënimi”) and Like a Prisoner (“Jetë burgu”) have been translated by John Hodgson. Harold SEGEL has published an anthology of Eastern European prison literature that includes many Albanian authors such as Maks VELO (1935-2020). Even though not a victim himself, Ismail KADARE has published the novel “E penguara” that deals with a woman in internment; the book was published in English as A Girl in Exile, also translated by Hodgson.

The goal should be to create a culture of remembrance, in order to prevent history to repeat itself, to take lessons from the past, to understand social and political difficulties of the transition period, and to integrate the past into the present, rather than to exclude it – by excluding, suppressing it, the past will still be there, and even more troublesome (cf. Lubonja 2022, 225).

Bibliography

Kienzle, Florian. 2023. Vom Wehrturm zur Streichholzschachtel – Orte und Räume in der albanischen Literatur. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Lachmann, Renate. 2019. Lager und Literatur. Zeugnisse des GULAG. Konstanz: Konstanz UP.

Lubonja, Fatos. 2022. Like a Prisoner. Stories of Endurance. Translated by John Hodgson. London: Istros.

– 2009. Second Sentence. Inside the Albanian Gulag. Translated by John Hodgson. London: Tauris.

Segel, Harold B. 2012. The Walls Behind the Curtain: East European Prison Literature, 1945–1990. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Velo, Maks. 2010a. Spaçi. Tirana: 55.

– 2010b. Hetimi. Tirana: 55.

– 2018. Përkthyesi. Tregime. Tirana: MAPO.