Relying on our forces

The Albanian way of development

Albanian road

The change of productive relations and the practice of the state-planned economy were for the communist leadership the premises for the implementation of its economic-political concepts in the field of industrialization. Through the state economy, it aimed to determine temporarily the key points of development of different economic sectors without causing significant disproportions in the overall economy. The speed of agricultural development was adapted to the pace of industrial development. Agriculture on the other hand was oriented towards domestic needs, i. e. the goal was the food self-sufficiency of the population. In the policy of industrialization, heavy industry had a long-term priority, except that the course followed differed from the Soviet or Chinese one. In these countries, the leaders had intended from the beginning to build the complete cycle of heavy industry in a parallel way. In Albania, this goal was tried to be achieved in stages, although the ultimate goal, the creation of heavy industry, was clear from the beginning.

Hoxha’s role in determining economic priorities seems to have been less dominant than has been claimed so far. The testimonies of former participants in the top governing structure question the alleged idea of a leader who had and wanted to have the last word on all the important issues.

As was the case in the other socialist states, economic plans were processed by the State Planning Commission (ALP), while its proposals were discussed and decided upon at the Council of Ministers. Then the plan was voted on at the Political Bureau. Its realization had to prove the justice of the line followed by the party leadership.

Regarding the issue of financing industrialization plans, the leadership of the ALP started from two phases: In the reconstruction phase, the budget for socialist accumulation had to be created with the help of nationalization of the most important industries, expropriation of political emigrants and collaborators and progressive taxation of the remaining capitalist sector (especially the “war speculators”). There were also proposals to limit domestic consumption. During the second phase, the so-called “phase of creating the economic basis of socialism”, the industry had to self-finance its consolidation by selling its products (Ruß 1979, 144). This concept could only be realized if the Soviet Union and other socialist countries supported Albania with mass economic aid, which played an important role in the elaborations of the leaders at that time (Hoxha 1969, 135).

During the socialist regime, the course of industrialization underwent various deviations and corrections, which had many causes. First, the experimental character of Albanian industrialization policy contained flaws that originated in erroneous concepts of economic policy. It was important to correct these soon to limit as much as possible the negative consequences. An example of this is the change in investment priorities during the first five-year plan 1951-1955. The relations with other countries and the efficient cooperation with them was another important factor that could impact the economic course of the Albanian communist regime. Relevant relations were severed if they did not meet expectations or jeopardized independence. In such cases, divergences have emerged within the Party, the results of which have massively influenced the concept of development (Ruß 1979, 141).

“Relying on our forces”: Objective or result?

While the Soviet Union had linked its further aid to political and economic policy changes, the Chinese leadership was prepared to provide support without fulfilling any economic or development policy preconditions. She was looking for allies against the Soviet Union. However, the invasion of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia, the Soviet-Chinese border conflict in 1969, and Soviet threats of a nuclear attack caused the Chinese leadership to rethink its foreign policy course. China showed itself interested in cooperation with the USA, tried to improve its position among Third World countries, and pushed Albania into an alliance with Romania and Yugoslavia to counteract Soviet influence. This alliance did not correspond to the intentions of the Albanian leadership.

It gradually became clear that China could not and did not want to fund indefinitely the industrial projects of the Albanian communist leadership. Beijing had already planned since 1972 to reduce its economic aid to Albania, something that directly impacted the sixth five-year plan. Hoxha must have become aware of the consequences. He had to either seek economic aid from Western countries, improve relations with the Soviet Union, or find new partners who were willing to support the industrialization policy of the Albanian Party of Labor (PPSh).

To avoid becoming too dependent on China, it was necessary to look for other economic partners, and this was attempted in Tirana by intensifying foreign trade relations with the West and the socialist countries between 1973 and 1975 (see Table 1). Difficulties in increasing the sales in the market may have prevented the growth of the exchange of goods. In addition, there were high-ranking politicians within the PPSh who were not prepared to support the previous priorities in industrialization policy.

This included the group of so-called “Saboteurs in the Economy.” The most prominent figures of this group were Abdyl Këllezi (chairman of the SPC since 1968), Koço Theodhosi (Minister of Industry and Mines since 1966), and Kiço Ngjela (Minister of Trade since 1954). They had opposed the breaking off of the relations with the Soviet Union because they believed that this would have dire consequences on the Albanian economy. They also considered the primacy given to heavy industry as mistaken and lobbied for the allocation of the main share of the investments in the light industry and agriculture.

The proponents of heavy industry (Hoxha and his followers) prevailed. One consequence of these power struggles within the PPSh leadership was Article 28 of the constitution adopted in 1976, whereby Hoxha’s ideas about preserving Albanian sovereignty determined the future course of the Albanian leadership even after his death (Bici 2007, 97).

Table 1: Albania’s trade volume in the years 1976-1983 (in percent)

| 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | |

| OECD[1]

Yugoslavia Comecon China Developing countries |

25

6 36 31 2 |

38

9 33 16 4 |

40

9 38 9 1 |

43

13 39 – 5 |

37

20 35 – 8 |

39

20 36 – 5 |

39

21 36 1 3 |

37

14 44 2 3 |

Source: Masotti-Cristofoli 1985, 305

But did the course of politics followed by the communist leadership aim at an autarkic economy detached from the outside world? This issue deserves careful consideration. In the scientific literature, different names are used to define the Albanian concept of economic development: “autarkic” (Wildermuth 1995, 51-61), “oriented towards the independence of the economy” (Ruß 1979, 304-315), or “self-reliant” (Kaser 1993, 301-303). But it is difficult to characterize the economic policy pursued by the leadership of the PPSh throughout the era of Albanian state socialism as an “attempt at autarky”. In the conditions that prevailed in the country in 1944, for the new rulers every concept which preached an autarkic economy should have seemed very unrealistic. In addition, autarky did not seem necessary as Albania was part of the socialist camp.

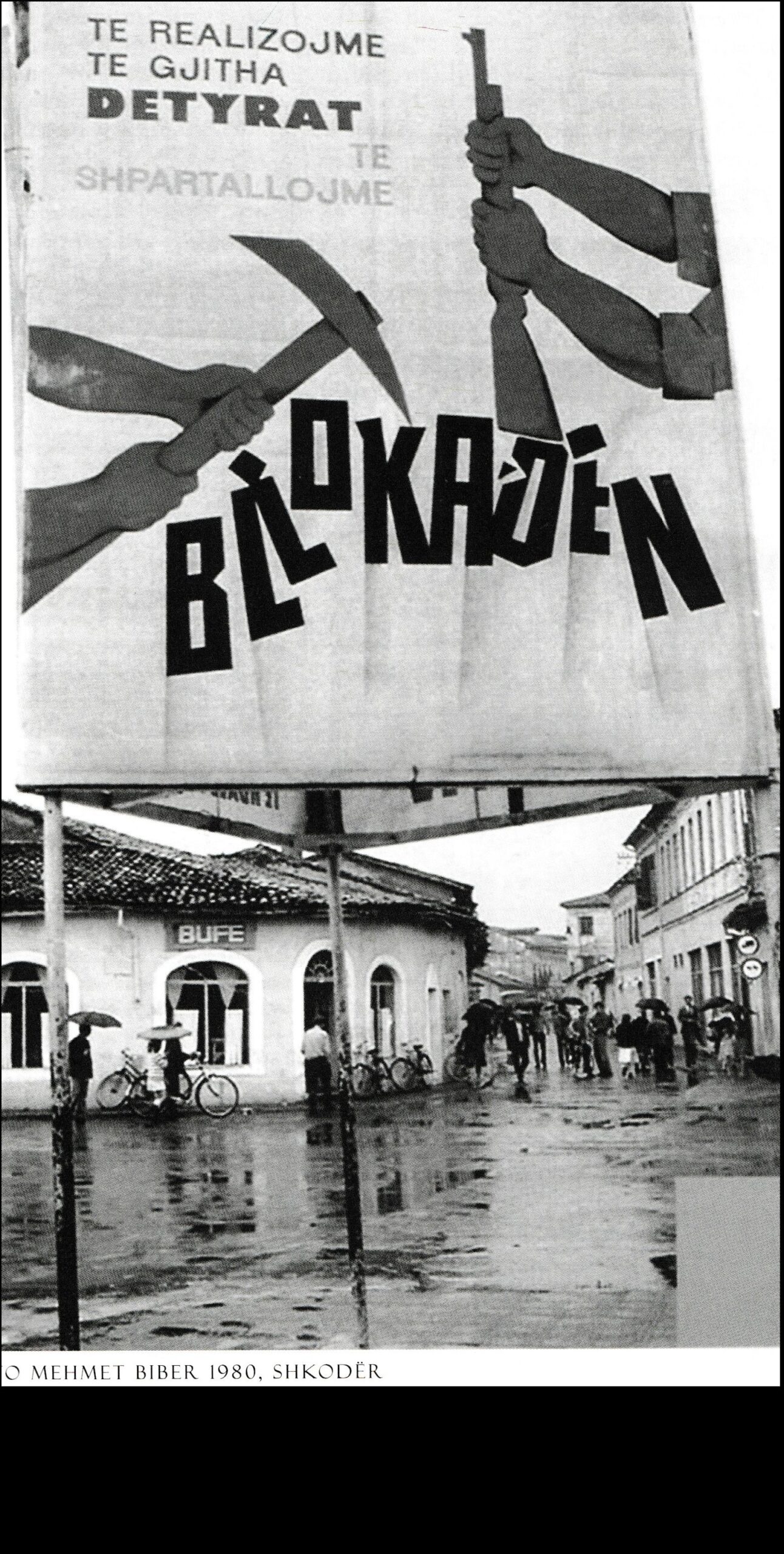

The “Rely on Our Forces” – creed began to become part of Albanian socialist jargon in the early 1970s and was born out of necessity in 1961 when the Soviet Union withdrew its support from Albania (Backer 1982, 356). It was the time when Enver Hoxha’s slogan began to be propagated: “We will eat grass and we will not violate the principles.” So “self-reliance” did not necessarily mean in the minds of leaders building an independent economy that would produce everything it needed.

Foreign aid was not initially rejected but accepted if the political leadership considered it “sincere”. This usually happened only when it came from the governments considered allies of the Albanian communists, whether from Yugoslavia at the beginning of the PPSH rule, from the Soviet Union, or other Eastern Bloc countries in the 1950s and then from the People’s Republic of China.

For both the socialist countries of Eastern Europe and most developing countries, industrialization was sometimes seen as an important step towards strengthening their sovereignty, since in the eyes of their governments, economic independence was the prerequisite for national independence. Communist Albania was no exception, but the new rulers, aware of their country’s backwardness, did not try to achieve autarky, despite the euphoria created because of rapid economic progress. Both Hoxha and other members of the Politburo warned against expecting Albania to achieve autarchy. In their eyes, it was very important to get the most out of the economy, but autarky was seen as “a goal that does not correspond to [the] reality and objectives.” (Nonaj 2020, 71)

Table 2: Estimate of foreign aid to the Albanian economy

| Giver | Period | Total (in Millions of Dollars) |

| UNRRA | 1945 – 1948 | 26* |

| Yugoslavia | 1945 – 1948 | 33** |

| USSR | 1947 – 1961 | 156 |

| Other Eastern European countries

1948-1961 |

1948 – 1961 | 133 |

| China | 1959 – 1975 | 838 |

| Western trade credits | 1965 – 1975 | 94 |

* Of which 20.4 million came from the United States.

** Additionally, technical, and military assistance was worth approximately $100 million.

Source: Kaser 1977, 1335

The intention to cover the domestic needs of grain without outside help was not only an expression of the communist ideology for the priority of economic independence but was also born from the experience with the Albanian-Soviet relations. Let’s take a concrete case: In the winter of 1960, the Soviet Union cancelled urgent grain deliveries needed by the Albanian government due to the drought. With the help of China, the shortages were compensated. Such situations were not allowed to be repeated because they posed unpredictable dangers to the regime.

If one looks at the economic statistics and the public speeches of Albanian leaders, one can see that a balanced balance of payments was the guiding principle of Albanian economic policy during the period of “splendid isolation”. It became an end in itself, ultimately with tragic consequences.

Article 28 of the 1976 constitution and the country’s low foreign exchange reserves did not allow the growth of foreign trade, so the cessation of economic aid from China had a significant impact on Albanian industry. Now, for the first time, Albania relied “on its own forces”, which was not the aim of the communist economic policy in this form (Schönfeld 1993, 439-451) but was due to the circumstances. The authorities had politically put the country in an offside position. However, the researcher gets the impression that Hoxha has assumed that such a situation was unstable in the long run. Even during his lifetime, the Albanian economy was heading towards disaster.

For this reason, the British scholar James F. Brown supports the thesis that Hoxha sought perspectives for the survival of the Albanian economy in three directions: a) intensification of economic relations with third world countries; b) partial improvement of economic relations with China; c) improving economic relations with the West (Brown 1988, 379). But Hoxha died before they were put to life. Under his successor Alia, the focus shifted to the light industry and the investments of capital in heavy industry shrunk, as this was costly and could not be implemented without foreign aid. But Albanian industry was wasting away, the need for capital was particularly urgent, and changes in economic and foreign policy were very reluctant, so the system could not survive the collapse of the socialist bloc in Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

Bibliography

Backer, Berit. 1982. „Self-Reliance under Socialism. The Case of Albania.” Journal of Peace Research 19 (4): 355-367.

Bici, Rozeta. 2007. Industrializing Albania during Communism. Case Study: Elbasan 1960-1991. Master thesis. Central European University, Budapest.

Brown, James F. 1988. Eastern Europe and Communist Rule. London: Durham.

Grothusen, Klaus-Detlev. 1993. “Außenpolitik.” In Albanien, edited by Klaus-Detlev Grothusen, Südosteuropa-Handbuch, Vol. 7. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 86–156.

Hoxha, Enver. 1969. “Raport i mbajtur në Plenumin IV të Komitetit Qendror të PKSh” [Report Held at the Fourth Plenum of the APL’s CC]. In Vepra, Vol. 3. Tirana: 8 Nёntori: 127-165.

Kaser, Michael. “Economic system.” In Albanien, edited by Klaus-Detlev Grothusen, Südosteuropa-Handbuch, Vol. 7. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993: 289–311.

Kaser, Michael. 1977. “Trade and Aid in the Albanian Economy.” In East-European Economies Post-Helsinki, edited by US Congress. Washington: 1325–1340.

Masotti-Cristofoli, Angelo. 1985. “Albania’s Economy Between the Blocks.” In Reform und Wandel in Südosteuropa, edited by Roland Schönfeld. München: R. Oldenbourg: 285-304.

Nonaj, Visar. 2020. Albaniens Schwerindustrie als zweite Befreiung? „Der Stahl der Partei“ als Mikrokosmos des Kommunismus. Berlin / Boston, De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

Ruß, Wolfgang. 1979. Der Entwicklungsweg Albaniens. Ein Beitrag zum Konzept autozentrierter Entwicklung. Meisenheim am Glan, Anton Hain.

Schönfeld, Roland. 1993. “Außenwirtschaft.” In Albanien, edited by Klaus-Detlev Grothusen, Südosteuropa-Handbuch, Vol. 7. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 427–451.

Wildermuth, Andreas. 1995. “Sich stützen auf die eigenen Kräfte”. Die Wirtschaftspolitik Albaniens nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. München, LDV.

[1] Above all Italy, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, and Greece, to a lesser extent Austria, the USA (indirectly), Sweden and Japan. Masotti-Cristofoli 1985, 292.