Encorporation

Southeastern transformations as objects, subjects, and principles of study

How are the world and our methods to encounter it bound to each other?

Until relatively recently, western academic Zeitgeist strove to render this kind of question obsolete: „The“ scientific method, it went, is to deliver objective facts about the world, the researcher is an outside, neutral, rational observer. His (yes, mostly his!) work provides us with the very mechanisms of the world’s functioning, necessary to make prognoses and to model reality to humankind’s best use. Politics was to govern. Arts was to draw a picture, to make a sculpture. Architecture to plan houses. Everything became a function, a „to“.

Interestingly, this kind of rampant positivism, this holding on to the idea of objective, observable truth, seems to be especially endurable in the social sciences, and particularly in my discipline, political sciences. (western) Mathematics know latest since Gödel, physics since the emergence of quantum physics, that human being and knowing is inescapably situated within the reality it studies, with all the limitations, the tensions, the undecidabilities that come with that epistemological realization. (especially eastern) Philosophy knew all along. Even if a single truth exists, we, human beings, are not capable of observing it objectively – which is proven by neuroscience, ironically. [1] Everything we know is shaped by subjective experience, context, and perception, and every knowledge shared shapes the reality it is making statements about, and it shapes the experience and perceptions of whoever perceives it.

This is hurtfully true also for the „to“- society, shaping and evaluating each and every thing according to its function, as directed towards a scope. Studying transformations that way, studying change, is not focused upon the very processes happening. Instead, this kind of study evaluates the efficiency of the movement towards a predefined telos. Objectivizing this kind of study, making it superior towards other epistemologies, is a power move, maybe a most basic one: proclaiming that „there is no alternative“. Objectifying societal transformation and its actors leads to a claim of knowing in advance the processes to be observed, and the motivations and goals of people involved, eventually striving for (normative) assessment of the observed. This conceptual logic is one of ranking orders – as seen in the manifold indices providing an account of who is doing „best“ and „worst“ in terms of „human development“, „freedom“, „economic growth“, „democracy“, and so on and so forth.

Protest against corruption – Bucharest, January 2017 – Piata Universitatii, photo Mihai Petre, wikimedia commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Protest_against_corruption_-_Bucharest_2017_-_Piata_Universitatii_-_5.jpg

Protest against corruption – Bucharest, January 2017 – Piata Universitatii, photo Mihai Petre, wikimedia commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Protest_against_corruption_-_Bucharest_2017_-_Piata_Universitatii_-_5.jpg

When, in 2017, for once Romania appeared in German news media (apart from the customary announcements about „Gammelfleisch“ and „Sozialschmarotzer“), because hundreds of thousands of people had gathered in all the bigger cities of Romania and all the bigger centres of Romanian diaspora to protest, the „surprise“ was characteristically condescending: questions like „What’s up in Romania? What is happening? What do these people want?“ were asked mostly rethorically. Because the answers were already known, as anything is already known about the east in the west, by definition. Because it is the east that needs to „europeanize“, which doesn’t actually mean to become more European, but to become more German. And we already know what that is. Romanians, even after over 30 years of „catching up“, don’t. All that Romanians – a people with high degrees of mobility, multilinguality, living in a multicultural and multiethnic state in the middle of European history and geography – can want is more „europeanization“. Which is foremostly to escape the world of post-socialist „legacy“, the apathetic society, the corrupt government, and to become a „civilized country“. Accordingly, some Romanians finally woke up – most likely the young, white, well educated urban men, who likely studied somewhere elsewhere. The German newsmedia’s surprise about their awakening was condescending in that it was like patting a kid on their head for learning a thing a bit earlier than the adult thought they would. And it is easy to prove these answers, scientifically, when you know where to look for them. They are not wrong, by the way! [2]

However: that using EU symbols, writing adresses to European institutions, translating slogans to english and demands to western narratives etc. was in part also a strategy of Romanian adults to generate international attention – is a different story. That East European political leaders welcome the anti-corruption discourse for being much easier derailed and put up against some individual opponent than discussions about political and economic contents is another different one. That protest doesn’t always show in street demonstrations, that protesting’s demographics, demands, and stances are much more diverse than the filters of publicity make it seem – are yet different ones. These stories will not be known by a political scientist trying to take herself out of the equation, fearing her own positionality, evading to „distort“ her field of research by her presence in and closeness to it.

And it is only one side of the problem that „we“, scientists, or the German public, don’t get to know them. The purist positivist approach (that believes its assumptions instead of handling them as presuppositions) also reiterates the distinction between world and ways of getting to know, and reproduces the hegemony inherent in that.

So, where are them alternatives, how could we look at the world differently?

One alternative I want to propose is a logic of encorporation: of making the object of study simultaneously the subject of it.

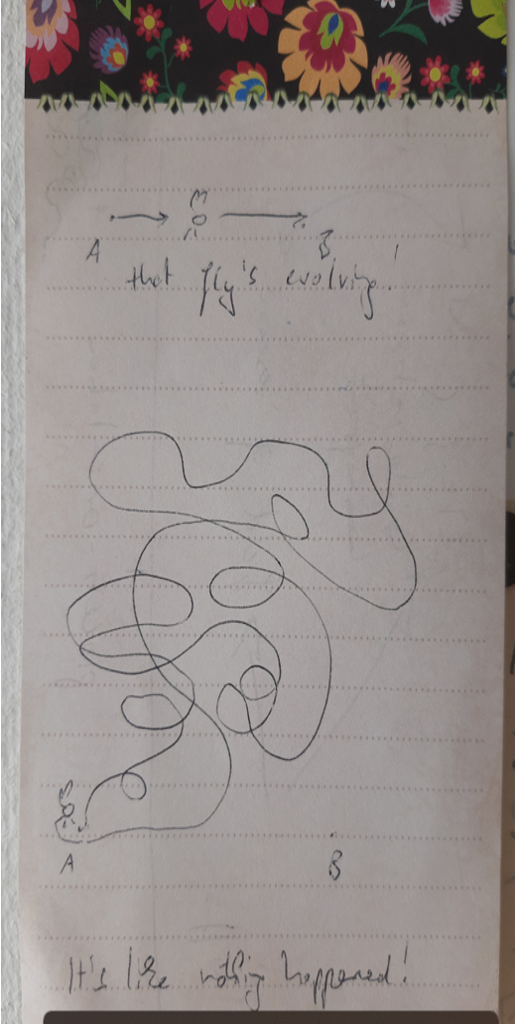

1) „that fly is evolving!“

2) „It’s like nothing happened!“

Author’s jot note

Instead of measuring inputs and outcomes, drawing straight lines between them, we can try to stick with the agents of our interest and see where they take us, and how, on which ways.

When coming to Tutzing in autumn 2023, I had thought about this idea, and its methodological implications, already for some time, with regard to my study of recent protest outbreaks in Romania and the interconnected shifts in Romanian political culture, and contentious politics in paticular. I had combined efforts with Romanian documentary filmer and self-denominated „political nerd“ Sergiu Zorger, to set up a living protest archive, online, a project we call „o altă poveste” – a different story, or another story. The idea is, instead of trying to pick the few dispersed pieces of the complex puzzle one person can individually see and carry, to create and facilitate a space for learning together. In which everyone interested could contribute. In which there would be space for contradiction, tension, and diversity, and that would be changeable – according to what users would contribute to it, and according to the feedback of the various activists we consulted for building the platform. Somehow, in my head, terms flipped: When my university would call such collaborative digital projects „science communication“ – actually a code for „nice-to-have-stuff“ – and conceives of papers in peer reviewed journals as THE measurement of scientific productivity, I would now put it the other way round: Science becomes doing collective learning, using my training, time, and other resources for facilitating it, letting myself and the image presented be changed by my now subject of study. Writing papers is still important – whilst I would conceive of these papers as „science communication“ – communication with peers, mainly dedicated to theory building, methodology, and indications where to have another look at things.

In Tutzing, I loved to learn that this kind of study was not at all limited to scientific research, and that the encorporation-thought itself had passed through many minds before mine. I learned that „subjects“, or agents, are not always humans. Houses can be subjects. Histories and spaces can be. Practices can be subjects.

Even the refusal to do something can be: in his artictic intervention, for example, Antoni Rayshekov makes the silence of politicians the subject of his study. In „the evasive choir“ [3] and „the evasive choir – remixed“ [4] he creates a setting in which the story of Bulgarian post-socialist transformation is told through politicians’ refusal to talk about it, through the silence of those of all people who are assigned to decide, to take responsibility. The harrumphings and hawings translate the political dissonance to an acoustic one – loud silence. The artist himself doesn’t „tell“ us anything, instead, he uses his skill to display a tension, creating and facilitating a space for thinking, for associating and interpreting, leaving it open to the viewer to explore and add up to the study of that tension, and of the societal context it represents.

The arts is not the object, the installations Rayshekov made. Encountering a work of art, one that manages to catch me, I usually feel how I felt when, as a child, I was handed a caleidoscope for the first time: the world that seemed so set, so understood to my eyes suddenly became strange, coloured, fractured, it suddenly became many worlds at once, or, at least, many perspectives upon it became visible. The tin cans used as speakers in the first installations – Rayshekov claims that all of these were emptied by himself personally – give (me) an association of ready-made, processed, all-the-same, maybe resignation. The second version of the installation remixes the sounds rhythmically, and repeats the sample on an old record player. What does that mean for politics? What does it mean for transformation, for societal change? How does such a post-socialist fragment compare to the socialist past? The installation made me think directly of the Romanian expression „wooden language“ [5], describing the sometimes fascinating skill of communist politicians to use many words without saying anything. What did the people in Rayshekov’s installation say between the sounds they made? What did those sounds mean to them, and what kind of context did they build for the things said in between? What would they have said instead of these sounds, being sincere?

The work employs its subject also as a principle of action: it evades any clear statement itself, any context for the sounds given. It repeats a processed „meal“, an already heard record, amplifying the refusal, the evasion, the silence of its creators. It questions transformation, contrasting its assumed dynamic, disruption, and hope, with an everyday dullness. Thus, in my interpretation, Rayshekov encorporates the object of his study, making it simultaneously a subject (evoking thoughts in the viewer and listener) and a principle of this piece of art.

Another take on encorporation I found in Dragana Konstantinović’s and Miljana Zeković’s presentation on their architectural approach towards renovating socialist buildings in the city of Novi Sad.[6] Instead of understanding renovation as „repair“, as going back to an imagined „original state“, rendering the present dereliction a deviance from „normality“, they decided to take on the whole reality of a building’s lifetime, to bring its history over to a renewed state. Together with their students, Konstantinović and Zeković studied socialist modern buildings in their city from the inside, using the state in which they found them as rich inspiration for artistic work, fotography, historical research, and, eventually, their architectural work. Collecting artefacts from abandoned houses, crafting artistic studies and drafts to catch their athmosphere, zooming in to levels of detail, traces of use, or zooming out to the building’s position in the urban landscape, its historical, social, cultural, political background, studying its shapes, the incidences of light, the colors and textures of the building, they got their inspiration for translating the multiple pasts, the „wanted“ as well as „unwanted“ histories of the buildings, to a new present. So, again, someone made the object of study a subject: they used the buildings as a site for (self-)education, for research, for creativity, letting the „other“ change the self. And, again, transformation becomes also the principle of the study: architecture, in Konstantinović’s and Zeković’s approach, is not about making up something, about building a house. It is about transforming a space, reaching well beyond the individual house, in which the self is embedded; and in displaying the transformation of the space through that process. What in scientifical work oftentimes sounds as giving up oneself into the infinite play of meta-levels, becomes plastic, literally tangible, in the work of architects.

This notion reminds me again of the object, subject, and principle of my own discipline, as I conceive of it: the political. The political condition is a tensionate one. It prescribes the organization of collective life, in light of the contingency and undecidability of its alternative ways, but given a necessity to make decisions between them, and to legitimate these decisions. Politics does take real forms – even if its ontological condition seems incommensurable. We can study politics, but, I argue, we should never forget, even if it’s „unwanted“, and definitely uncomfortable oftentimes, to also study the political: to ask for the potential alternatives, to consider tension, conflict, diversity, contention. Deciding for one or another methodological approach is a political decision, as research, knwoledge production, information, does touch upon the organization of collective life, and as there is no „objectively“ right way to do it. Which does never let anybody off the hook for legitimating their choices!

Antoni Rayshekov could just have told me and the other attendants of his presentation about the hums and haws of the politicians in his country. Dragana Konstantinović and Miljana Zeković could have repaired some buildings in Novi Sad. I could have taken media articles, Facebook posts, or official documents as the sources for studying protests in Romania, Sergiu could have filmed them with his camera. However, we all decided to immerse ourselves, and this way learned about the diversity of contention, made silence audible, history tangible.

So, all of the crafts mentioned can use their skill and training, in specific ways, to study the world: (Political) science facilitating spaces for collective learning and confronting diversity; arts creating moments for reflecting own assumptions and interpretations, and for exploring new questions to be asked; architecture transforming physical spaces, through its aesthetics putting into dialogue the past and the present. All of these can take interest in transformation, as an object of their study. They can make transformation subject of their work, giving the world studied a place and a say in the study itself. And they can make transformation their principle of action, thoughtfully positioning within the world studied, taking on the own influence on it as a characteristic of the study, and reflecting it.

However, coming back to the start of this essay, thoughtfully: with all that has been said we must still acknowledge that, being part of the world we study, simultaneously we are also inescapably different from it, and we do make statements about it all the time. For communication, for action, for living we need shared images of the world. Research needs to be written down, arts objectified, houses built. Studying things only from within, we would miss out how they look like from the outside. What I wanted to elaborate was not at all the solution to the problems positivism poses. In a more agnostic sense, it was a pledoyer for considering other positions, to accept the multiplicity of world-images. And it was a proposal for one such possible other position to experiment with – one that fascinated me, and one that I feel connects many of the works presented at the Academic Week Tutzing 2023.

I thank Sergiu Zorger for reading and commenting the manuscript.

[1] For an impressively comprehensive (yet accessible for the interested non-neuroscientist) elaboration of that fact, check Robert Sapolsky’s „Behave. The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst“.

[2] The sarcastic tone of this paragrah stems from my frustration, as someone who grew up within the eclectic reality of post-socialist transformation, with the air of objectivity so many outside observers give themselves, with the ardently maintained rightfulness, the brute generalization carrying their ever-repeating (and sometimes self-fulfilling!) statements.

[3] See https://community.ulysses-network.eu/works/view/2960/

[4] Visit https://vimeo.com/871063161

[5] Originally „limbă de lemn”.

[6] They give an account of their methodological approach towards renovation here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374316735_Rethinking_Dissonant_Heritage_The_Unabsorbed_Modernisation_of_Novi_Sad, I also recommend visiting the website https://mismobaza.org/novi-sad-moderni-grad/, „Novi Sad-Modern City“ was a project both presenters collaborated in with the occasion of Novi Sad being European cultural capital, 2022.