A nationalist-conservative grammar of change?

How Bulgarian nationalists’ political discourses articulate the notion of ‘change’

1. Introduction

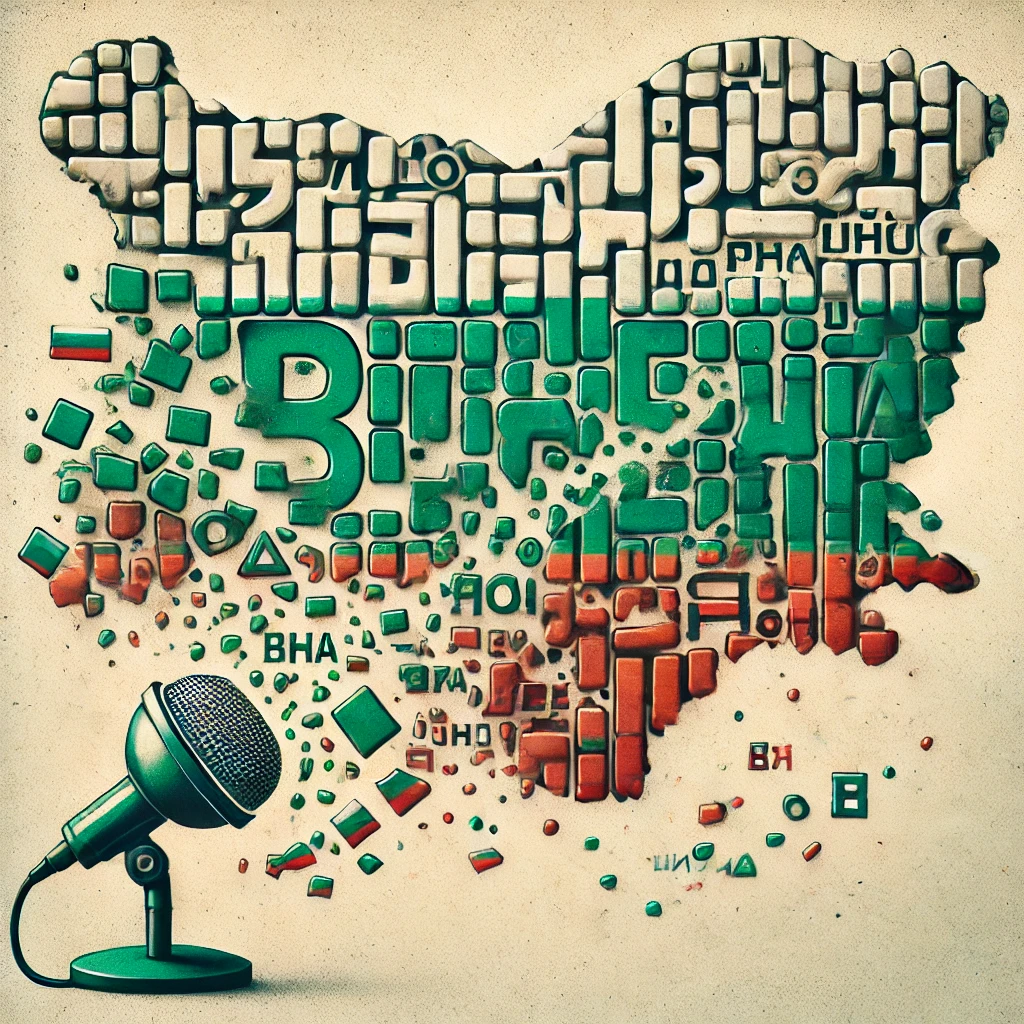

Since the end of real socialism, post-democratic (Krasteva 2019), clientelist and otherwise corrupt (Coalition 2000 2003; Benovska-Sabkova 2015; Price 2019) practices have defined Bulgaria’s political regime. Moreover, civil society – especially its ‘uncivil’ forms (Kopecky and Mudde 2002) – are kept in contempt by both political elites and mainstream media (Telarico 2021d). Thus, despite the many promises of the so-called ‘transition’ towards liberal-democracy (Melone 1998; Angelov et al. 2004) and recent episodes of grassroot mobilisation, the democratic potential of Bulgarian politics has remained largely untapped (see also Telarico 2022).

Yet, between summer 2020 and spring 2021, a series of protests drew tens of thousands into the streets of Sofia, the capital, and other major cities (Dnevnik 2020; BST’s Reporters 2020) generating a sensible democratising thrust. However, such bottom-up outbursts are usually neutralised by the inertia of dominant political culture (Sztompka 1993; McFalls 1995; Ådnanes 2007; Telarico 2021a, 100–102). Usually, social movements are ephemeral and lead to little more than the establishment of new, bigger or smaller, parties. Yet, decades of stagnating living standards and recent scandals (Telarico 2021b) mine the legitimacy of current elites making the opportunity structure more favourable to outsiders aspiring to ‘change things’ (Telarico 2021c). In fact, the most recent events have had some long-lasting effect, at least on the discursive level. In fact, the term ‘change’ has become virtually ubiquitous in Bulgarian political discourse, being uttered from both the left and the right of the political spectrum (Kodzhaivanova 2021; Petkov 2021).

Against this background, the political party Văzrazhdane (‘Revival’) represents an interesting case study due to its attempt to bring about ‘change’ while advancing a “conservative” (Kostadinov 2021a) and “homeland-loving” (Kostadinov 2021b) agenda. Even more so given that it has gained enough popularity for its role in the aforementioned protests that 14 of its members now seat in the National Assembly. In particular, this investigation asks how Văzrazhdane’s political discourse articulates the notion of ‘change’ in favour of less-favoured socio-economic groupings within its wider nationalist-conservative ideology. In doing so, the paper carries out an in-depth, discourse analysis of Kostadin Kostadinov’s – the party’s foremost personality, leader and founder – political discourse. Prospectively, this study helps shedding a light on how rightist subjectivities can centre their political discourse around the notion of ‘change’ in order to embedded traditional-left aims and policies on a nationalist-conservative political platform.

Due the amphiphilic nature of its object and objectives, this research transcends orthodox disciplinary borders between social sciences. Namely, it draws on Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) and its applications to political discourse in order to challenge the theorisation of rightist political subject upheld by much of the literature in political science and political sociology. In fact, building on seminal works in CDA and applied linguistic, one can argue that politicians’ use of language constitutes a specific social practice essentially indistinguishable from a material action. Hence, political discourses about change implies some sort of direct social change by themselves. All things considered, this section offers a theoretical justification for the analysis of Văzrazhdane’s political discourse about change as both a form of unmediated change and a tool “to project and shape conceptions of the future and their ideological implications” (Dunmire 2005, 483).

2. Theory and methodology

The choice of the methods, the methodology and the data used in the next section follows from the need to emphasise the nexus joining speech acts and other discursive practices with representations and narratives, on the one hand, and prefiguration of the future and political action, on the other. Unfortunately, there is not much extant literature from which to take inspiration or upon which to build. The most interesting resource is Maria Todorova’s “The Course and Discourse of Bulgarian Nationalism” (2019), a quite broad study on 20th-century Bulgarian nationalism. Other relevant sources focus on types of discourses associated with Bulgarian rightists as a category, rather than on a specific rightist subject (Tarasheva 2017; Stanoeva 2018). Moreover, Bulgarian political-discourse analyses tend not to have an unclear methodology and use a narrow set of methods within non-innovative methodologies

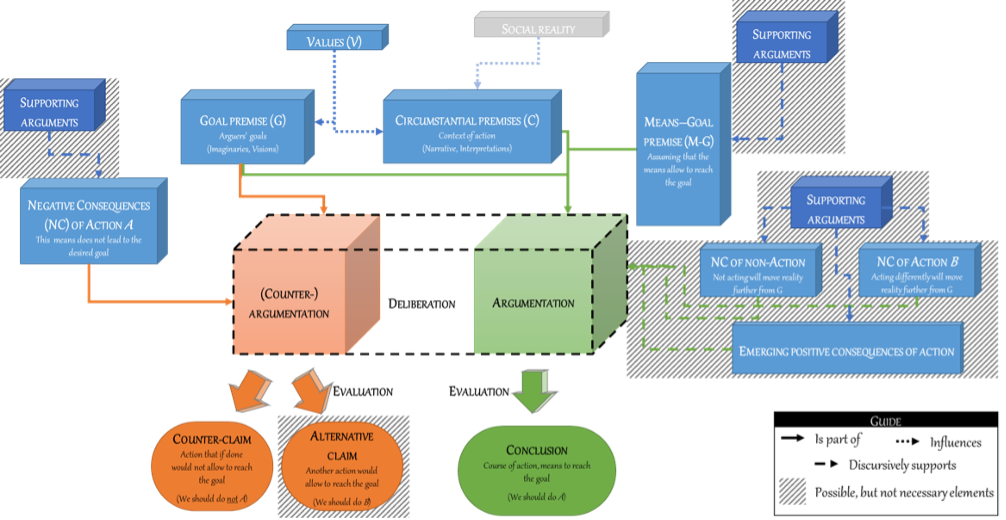

This paper adopts the framework proposed in Political Discourse Analysis by Isabela and Norman Fairclough (2012). Admittingly, the book takes a rather specific view of political discourse that allows to highlight and foreground the connection between political discourse and political action. Namely, a slightly more articulated version of the aforementioned methodology is used. First, a number of accessory elements to the original model figure explicitly in the analysis. Moreover, the relations between different components of the argumentative structure are distinguished in ‘inclusion’, ‘discursive support’ and ‘influence’. Finally, a clearer distinction between counter-claims and alternative claims whose evaluation is part and parcel of practical reasoning is proposed. In particular, this methodology allows to subsume “symbolisations”, “ideological interpretations”, “stories”, “perceptions”, and “narratives” as well as “imaginaries” and “strategies” (Jessop 2002; 2004) into argumentative discourse as “premises in arguments for action” (Fairclough and Fairclough 2012, 3).

The model of argumentative political discourse used for this research.

Using this model, the paper intends not to contest the shrewdness of either the premises nor the argumentative (de facto, political) conclusion of Konstandinov’s discourse — albeit this is possible. On the contrary, it intends to look at the premise-conclusion structure of Văzrazhdane’s discourse to excerpt the conception of ‘change’ underlying it.

3. Data and methods

The analysis focuses on two interviews with a combined duration of 1h46, transcribed to 2,602 words. The texts cover a narrow timespan from before Văzrazhdane became a well-known political subject to after it won seats in the parliament. Also it is worth nothing that unorthodox political interviews (46% of the words) are “a hybrid genre that is closer to talk show discourse” (Lauerbach 2004, 391), both online [Text № 1 (Kostadinov 2021a)] and in TV [Text № 2 (Kostadinov 2021b)] with a strong emphasis on argumentation and deliberation. Also, the effect of media-specific features is minimised allowing the basic feature of Văzrazhdane’s political discourse to emerge more clearly.

4. Analysis and findings — ‘Change’ in a premise-conclusion political discourse

The analysis of the selected text in search of clarifications regarding Văzrazhdane’s interpretation of the notion of ‘change’ consist in identifying the components of its premise-conclusion deliberation and analysing grammatical and linguistic features of the text according to a CDA techniques. The two interviews (text № 1–2) converge on the conclusion: “We need to vote for Văzrazhdane”. Clearly, there is an omnipresent alternative claim (“Vote for another party”) and an even more pervasive counter-claim (“Do not vote at all”). Interestingly, Kostadinov’s texts show a well-developed deliberative structure – possibly also thanks to the specificities of this hybrid genre – in that they justify the conclusion by arguing that Bulgarians need to vote for Văzrazhdane “[b]ecause there is no one else and because only we can” change the status quo (text № 1, line 234).

Overall, both the diagnosis contained in the C premise and the arguments offered to support the M-G premise devaluate the alternative claim on the basis of a precise set of values. At first sight, it may seem that the values Kostadinov’s claims are rather backward-looking, fitting the traditional description of the political right as a reactionary and reactive actor: the ideal of the 19th-century “Bulgarian Revival” (line 35), equality (30–31), family (3, 111–4, 136–40) and an unspecified self-identification as a “conservative organisation” (line 161). However, the value most often remarked by Kostadinov reveals a much more future-oriented perspective and a strong advocacy for Bulgarians to start working to change both their life (henceforth: ‘inward change’) and Bulgarian society (hence: ‘outward change’). In a word, this tension could be well summarised under the Nietzschean label “will to power” (Wille zur Macht). Notably, this notion is employed both in the narrower sense of humanistic self-perfection (Nietzsche [1887] 2007, 48–50 chap. 2 para. 11) and outward, political project for the affirmation of one’s own morals (Nietzsche [1913] 2016, 2:121, section 636).

Discursively, this ‘driving force’ is presented in multiple ways and using some very articulated metaphors. At first, Kostadinov associates the claim of being “different” from other parties with the voluntaristic nature of Văzrazhdane [it “is an organization created solely by volunteers and to this day we are just that” (lines 1–2)]. In addition, he utters a deeply emotional encomium of willpower by remarking even though many “are disillusioned with what is happening in the country and deceived and lied to in their hopes” (lines 6–7), individuals remain capable of inward and outward change

Also, he reinforces the necessity of being strong-willed by using the metaphor of ‘politics as a fight’: “It’s not shameful to be beaten by someone stronger — shameful it’s only to run away” (lines 227–8). This fight-themed metaphor frames politics in “stereotypically masculine ways as battles, sporting events or back street brawls” (Gidengil and Everitt 2003, 561) and constitutes the intertextual references of one of Kostadinov’s subsequent speeches, in which the role of ‘will’ is lionised: “Today our nation deserves new, decisive and outspoken leaders and it is high time that Bulgarian politics be guided by worthy men” (№ 5, 9–10).

This exaltation of willpower builds upon a combination of claims based on Kostadinov’s personal expertise as a historian and PhD in ethnography and authoritative intellectuals from the past.

In support to this conception of a ‘malleable’ history, Kostadinov uses also an authority claim based on common sense or ‘popular wisdom’ (“the smart one learns from the mistakes of others, the stupid one learns from his own mistakes, and the idiot doesn’t learn at all — he repeats them”, lines 85–86); which builds up the positive self-representation of an attentive and modest orator. In addition, all the texts show authority claims employing quotes by figures from Bulgaria’s contemporary history. Namely, in order to weaken the traditional definition of ‘rightist’ it is worth mentioning here that Kostadinov proudly quotes leftist thinkers like the poets Geo Milev and Radion Ralyn almost off the top of his head.

4.1 “Change is the only choice” and “we are the alternative” — Text № 2

In sum, strongly emotional appeals constellated various sort of authority, common-sense and expertise claims in the first text. And this feature appears even more marked in Text № 2, Kostadinov’s first interview on the Bulgarian National Television’s popular weekend-morning talk show Denyat zapochva s Georgi Lyubenov [“The Day Begins with Georgi Lyubenov”]. In this case, the interviewer’s role was more incisive than in Text №1’s: the questions were more pressing and Kostadinov was usually not allowed to dwell on his favourite talking points for too long. Yet, this does not weaken the perceptibly of Văzrazhdane’s political discourse. On the contrary, it enhances its deliberational component insofar as Kostadinov was forced to dismantle the alternative claim that Bulgarian voters should prefer other rightist formations.

However, unlike the previous one, text № 2 operates mostly the negative representation of other political subjects in order to waken the interviewer’s alternative claim that “everyone plays in that field [viz. the nationalist right]”. In particular, Kostadinov remarks that Văzrazhadane is the only political party to “work persistently” towards outward change (lines 1–2). But then moves to the justification of the conclusion “we need to vote for Văzrazhadane” arguing that this is a necessary mean to reach the abovementioned goals. Namely, Kostadinov criticises both main components of the Bulgarian right: the “classical right” (118) and the nationalist forces gathered around the VMRO party. First, he jokes about the former’s total disconnect from Bulgarians’ reality (118–9)Then, he accuses the VMRO of having sold their souls to the corrupt elite in power having “completely sold out and BETRAYED the interest of their voters.” (131–2) Finally, he does not spar an uppercut also to the meteoritic Ima takăv narod (ITN), a personal party established by popular folk singer Slavi Trifonov (for the first academic work in English on ITN see Telarico 2022). He accuses ITN of pointlessly appropriating folk songs: “I love to sing folk songs too. And even with great pleasure I know probably much more than a hundred songs […]. But that doesn’t mean anything actually” (153–5). In particular, he emphasises that Mr. Trifonov’s statement that

“Bulgaria’s membership in the European Union and NATO is WITHOUT-ALTERNATIVE […] cannot be accept by the ordinary […] Bulgarian citizen, who defines himself as a patriot, a lover of the homeland [rodolyubets], a nationalist.” (Text №2, lines 159–61)

Văzrazhadane, our consistent policy, which has not changed since we established our organisation in 2014” (138), voters should realise that “we have no other choice” (181), but to accept Kostadinov’s conclusion that voting for Văzrazhadane is a necessary action to bring about outwards change.

5. Conclusions

This researched started inviting to rethink the traditional definition of left and right as synonyms of, respectively, “progress” and “reactionism”. In order to justify this claim, it offers a summary of the currently lacunose understanding of the political right in the social sciences. In particular, it underlines the many obstacles that the academia as a collection of mostly ‘liberal’ researchers has met in addressing this topic. The scarce heuristic value of the rightist-reactionary equation is tested using a pragmatic combination of quantitative and qualitative methods for political-discourse analysis. In particular, the paper proposes a widened version of Fairclough and Fairclough’s (2012) framework for the study of political discourse as argumentative discourse — which is then justified a fortiori by the results obtained with CDA techniques.

The selected case study, the Bulgarian nationalist-conservative party Văzrazhdane is particularly suited to this research’s aims. In fact, the analysis of eight texts produced by its leader, Kostadin Kostadinov, between April 2021 and January 2022 reveal the total absence of blindly reactionary tendencies and ideals. On the contrary, both qualitative and quantitative techniques show that the topic of ‘change’ is central in the premise-conclusion structure of Kostadinov’s deliberations and highlight the positive image of ‘future’. Moreover, a lexical and argumentative analysis reveal that Văzrazhdane’s discourse focuses mostly on actions to be realised in the extra-discursive world and it is rich in speech acts.

Finally, qualitative CDA shows that Kostadinov emphasises constantly the role of ‘will’ in the realisation of change and the improvement of personal qualities. Partly, these ideas echo one of the many possible interpretations of Nietzsche’s Wille zur Macht. Hence, this paper ultimately suggests to open up the social sciences to theorisations and insights on the revolutionary nature of the political right provided in historical studies on fascism and national-socialism. Moreover, it recommends scholars not to be prejudiced and automatically expect a revolutionary right to be racist or Nazi tout court. In fact, for all its emphasis on change and nationalistic rhetoric, Văzrazhdane’s discourse pays no attention to ethnic and religious minorities. Perhaps, a non-genetic understanding of nations could achieve what some scholars obstinately pretend from a weakened left. Or perhaps not. But there is no justification for remaining blind to this scenario.

Bibliography

Ådnanes, Marian. 2007. “Social Transitions and Anomie among Post-Communist Bulgarian Youth.” YOUNG 15 (1): 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308807072684.

Angelov, Georgi, Lachezar Bogdanov, Martin Dimitrov, Asenka Hristova, Vladislav Slanchev, Krasen Stanchev, Georgi Stoev, Dimitar Chobanov, and Georgi Angelov. 2004. “Анатомия На Прехода: Стопанската Политика в България От 1989 До 2004 г. През Погледа На Института За Пазарна Икономика”. [Anatomy of the Transition: Economic Policy in Bulgaria from 1989 to 2004 through the Eyes of the Institute for Market Economics]. Edited by Institutŭt za pazarna ikonomika. 1st ed. Poreditsa Voĭni i Vlast. Sofia: SIELA. http://www.easibulgaria.org/assets/var/docs/ANATOMIA_NA_PREHODA.pdf.

Benovska-Sabkova, Milena. 2015. “Small Places, Large Networks: Transformation of Clientelism in Bulgaria”. In Klientelismus in Südosteuropa: 54. Internationale Hochschulwoche der Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft in Tutzing, 5.- 9. Oktober 2015, edited by Klaus Roth and Ioannis Zelepos, 31–48. Berlin: Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. http://eprints.nbu.bg/3902/1/clientelism_Tutzing1_ENG_Published.pdf.

BST’s Reporters, dir. 2020. ““Велико народно въстание – V” – Ден 100 на протеста “Народът срещу мафията””. [“Great National Uprising – V” – The 100th day of the protest “The People against the Mafia”]’. 16:9. Sofia: Bŭlgarska svobodna televiziya. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MuiWDJT3XGo.

Coalition 2000. 2003. “Доклад за оценка на корупцията 2003”. [Corruption Assessment Report 2003]. Sofia: Coalition 2000. https://csd.bg/fileadmin/user_upload/publications_library/files/2003/CAR_2003_BG.pdf.

Dnevnik. 2020. “Политическата криза: на фона на бурни протести управляващите опитват да печелят време (хронология)”. [The political crisis: amid violent protests, the government tries to buy time (chronology)]. 1 September 2020, sec. Na zhivo. https://www.dnevnik.bg/politika/2020/09/02/4108801_politicheskata_kriza_na_fona_na_burni_protesti/.

Dunmire, Patricia L. 2005. “Preempting the Future: Rhetoric and Ideology of the Future in Political Discourse”. Discourse & Society 16 (4): 481–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926505053052.

Fairclough, Norman, and Isabela Fairclough. 2012. Political Discourse Analysis. New York: Routledge.

Gidengil, Elisabeth, and Joanna Everitt. 2003. “Conventional Coverage/Unconventional Politicians: Gender and Media Coverage of Canadian Leaders’ Debates, 1993, 1997, 2000”. Canadian Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 559–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423903778767.

Jessop, Bob. 2002. The Future of the Capitalist State. 1 ed. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity.

———. 2004. “Critical Semiotic Analysis and Cultural Political Economy”. Critical Discourse Studies 1 (2): 159–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900410001674506.

Kodzhaivanova, Ani. 2021. ““Маркет Линкс”: Силно Желание За Промяна и Висока Подкрепа За Служебния Кабинет”. [“Market Links”: Strong Desire for Change and High Support for the Caretaker Cabinet]. Kapital, 11.6 2021. https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2021/06/03/4216711_market_links_silno_jelanie_za_promiana_v_obshtestvoto/.

Kopecky, Petr, and Cas Mudde, eds. 2002. Uncivil Society?: Contentious Politics in Post-Communist Europe. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203988787.

Kostadinov, Kostadin. 2021a. “Костадинов и Цанов: ОЧИ в ОЧИ – НАПРЕД и НАГОРЕ”. [Kostadinov and Tsanov: FACE TO FACE – ABOVE and BEYOND]. Interview by Stanislav Tsanov. 16:9. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLlnC46QXcE.

———. 2021b. “ПЪТЯТ НА ВЪЗРАЖДАНЕ”. [VĂZRAZHDANE’S PATH] Interview by Georgi Lyubenov. Bŭlgarska Natsionalna Televizia. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVl4irhVbZE.

Krasteva, Anna. 2019. “Post-Democracy: There’s Plenty Familiar about What Is Happening in Bulgaria”. openDemocracy. 20 November 2019. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/bulgaria-post-communism-post-democracy/.

Lauerbach, Gerda. 2004. “Political Interviews as Hybrid Genre”. Text – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 24 (3). https://doi.org/10.1515/text.2004.015.

McFalls, Laurence H. 1995. “The Cultural Legacy of Communism”. In Communism’s Collapse, Democracy’s Demise?, 139–65. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230373266.

Melone, Albert P. 1998. Creating Parliamentary Government: The Transition to Democracy in Bulgaria. Parliaments and Legislatures Series. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. https://kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/29453/CREATING_PARLIAMENTARY_GOVERNMENT.pdf.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. (1887) 2007. On the Genealogy of Morality. Edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson. Translated by Carol Diethe. Rev. student ed. Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press. https://philosophy.ucsc.edu/news-events/colloquia-conferences/GeneologyofMorals.pdf.

———. (1913) 2016. The Will to Power: An Attempted Transvaluation of All Values. Edited by Oscar Levy. Translated by Anthony Mario Ludovici. The First Complete and Authorised English Translation. Vol. 2. 2 vols. Edinburgh; London: T.N. Foulis. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/52915.

Petkov, Kiril, dir. 2021. “Промяната в България е възможна и не е толкова трудна” [Changing is possible and not so difficult in Bulgaria ]. Politicheski NEkorektno. Sofia: Bŭlgarsko Natsionalno Radio ‘Horizont’. https://bnr.bg/play/post/101519390.

Price, Lada Trifonova. 2019. “Media Corruption and Issues of Journalistic and Institutional Integrity in Post-Communist Countries: The Case of Bulgaria”. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 52 (1): 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2019.02.005.

Stanoeva, Elitza. 2018. “Хипохондрични идентичности: Джендър и национализъм в България” [Hypochondriac Identities: Gender and Nationalism in Bulgaria]. Sotsiologicheski problemi 50 (2): 715–35.

Sztompka, Piotr. 1993. “Civilizational Incompetence: The Trap of Post-Communist Societies”. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 22 (2): 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-1993-0201.

Tarasheva, Elena. 2017. “Дискурси на популизма”. [Discourses of populism]. Politicheskite Izsledvania, no. 1–2: 101–21.

Telarico, Fabio Ashtar. 2021a. “Digital Civic Cultures in Post-Socialist South Eastern Europe: Lessons, Prospects and Obstacles After Thirty Years of Media (Il)Literacy in the Region”. In Дигитална Гражданска Компетентност и Медийни Стереотипи [Digital Civic Competence and Media Stereotypes], 1st ed., 95–108. Montana, Bulgaria: Polymona. https://fatelarico5.wixsite.com/website/chapter-2021-2.

———. 2021b. “Bulgaria’s Pre-Electoral Tensions: From Constitutional Crisis to Institutional Trench War”. Global Risk Insights. 23 February 2021. https://globalriskinsights.com/2021/02/bulgarias-pre-electoral-tensions-from-constitutional-crisis-to-institutional-trench-war/.

———. 2021c. “A Leaderless Ship: The Bulgaria’s Political Crisis and the Storm to Come”. Modern Diplomacy. 15 May 2021. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2021/05/15/a-leaderless-ship-the-bulgarias-political-crisis-and-the-storm-to-come/.

———. 2021d. “Demythologising the “Russification” of Bulgarian Media’s Treatment of Civil Society: Analysis of the Transfer of Russian Mainstream News Media’s Cliches and Rhetoric on CSOs Upholding Human Rights and Environmentalism to Bulgaria”. Sofia: BlueLink Foundation. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5903390.

———. 2022. “There Is Such a People, but Is There Such a Party? The Case of “There Is Such a People” Lingering the Border between Party-Movement and Personal Party”. In Измерения На Свободата: Исторически и Културни Проекции [Dimensions of Freedom: Historical and Cultural Projections], edited by Maya Padeshka, Mladen Vlashki, and Fabio Ashtar Telarico. Vienna: Natsionalno izadtelstvo za nauki „az-buki“.

Todorova, Maria Nikolaeva. 2019. “The Course and Discourses of Bulgarian Nationalism”. In Scaling the Balkans: Essays on Eastern European Entanglements, 319–65. Balkan Studies Library 24. Leiden ; Boston: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004382305_019.