A Microhistory of the 20th Century

Spatial Transformation, Social Engineering, and the Industrialization of the Albanian Countryside

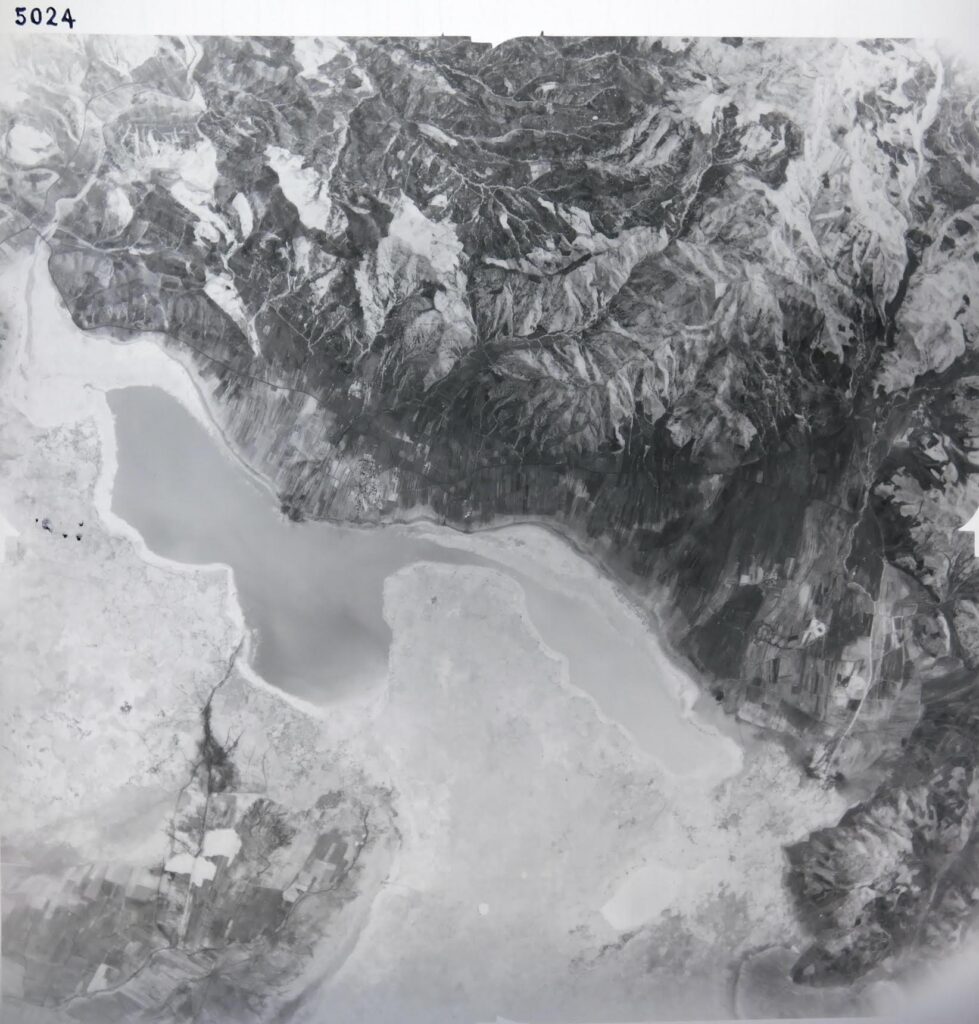

aerial photograph, USAF September 1943

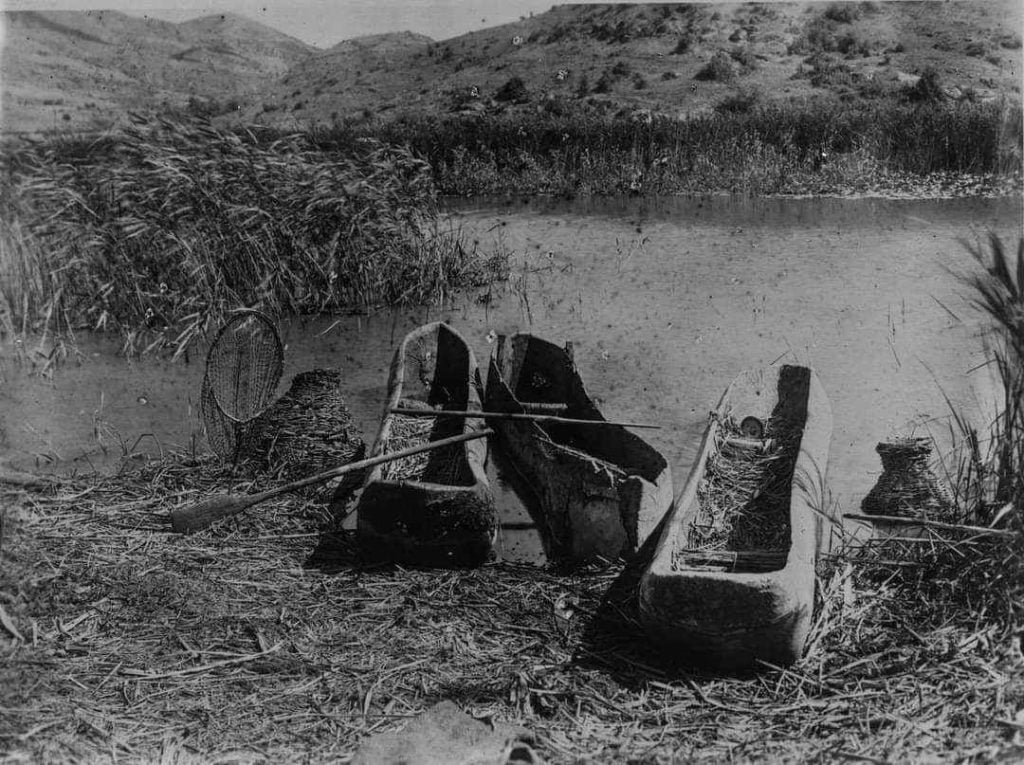

The plain of Maliq is located in Albania’s southeastern district of Korça. Surrounded by a crown of mountains, this plain was covered for thousands of years by a marsh called the swamp of Maliq. For millennia, at least since the Neolithic, this wide shallow pond, covered by reeds and a thick cape of vegetation, used to be the gravity center of the human communities that live around it. Cultures, languages, states, rulers, and beliefs changed across centuries and yet, the importance of the swamp remained unchanged regardless of the whims of history. The quagmire with its seasonal tides that followed the rhythm of nature looked majestically indifferent to the man-caused historical process. Humans and their culture were too small, too powerless to interrupt nature’s course. Not so in the late 19th century, and especially in the 20th century. At the moment Prometheus became the archetype of the new brave Faustian world committed to ousting and dethroning the old Gods from their Olympus and man decided to start his new modern adventure by subjugating nature, thus marking, under the banner of science the final triumph of culture over its eternal enemy, well, at that moment the days of the swamp of Maliq were counted.

fishermen boats used in the swamps, private collection

The project of reclamation of the marshland started in the last decades of the Ottoman Empire, was retaken during the interwar era by the authorities of the new and fragile Albanian nation-state, and completed by the communists in the first years after their takeover, as to prove the efficiency and the superiority of the new power structure as compared to its predecessors, which were slow, corrupted, and too conservative to launch forward with full force the project of progress. Indeed, progress meant the revolutionary transformation of society, culture, and nature; an increased pace of change that dwarfed the evolutionary path. The triumph of Man’s will expresses itself exactly in the acceleration of speed for reaching quicker the destination of earthly utopia. Thus, Maliq’s reclamation was part of those projects where man triumphed over nature, the death knell of backwardness and the shining ray of the bright future, which was approaching day by day. Maliq’s 20th-century history was not over with the reclamation.

After the swamp was gone, Maliq was transformed into Albania’s center of sugar production. Where once used to be the swamp, the communist regime built a sugar refinery and a small town named Maliq. Two other tokens of modernity made their way to the now ex-swampland. The tall chimneys that spilled the black smoke of progress and urban life. In the meantime, the whole plain was cultivated with sugar beet. Being an intensive-work crop, sugar beet required mechanized plowing, a dense watering system, and a large workforce. As a result, the communist regime established new villages and modern state farms that were some of the most profitable in Albania. Maliq became a sort of space for conducting an internal civilizing mission. The swampland resembled the borderlands in America and Eurasia, a space where nature was tamed and used for productive scopes. In the area that was once covered by reeds and stagnant water and where people moved walking or on oxcarts, now there were streets, trucks, and buses transporting people and goods, and tractors plowing the land. Maliq’s plain was filled with machines coming from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Germany – both GDR and FDR – or homemade. The land of sugar was transformed in less than two decades and its new technological landscape became an icon of the communist alternative to modernization and development. As a result, the social fabric underwent a full transformation.

reclaiming the swamp during communism, private collection

The new technocratic and working classes emerged in the area with relatively well-paid jobs that contrasted with the other surrounding areas, especially the highlands. Socialist development did not dodge the trap of spatial inequality. Meant as a humane alternative to capitalism’s multiple inequalities, socialism promised to undo all of them, from that between lower and upper classes, to gender inequalities, to that between city and countryside. However, as Maliq’s case shows, socialist industrialization did not fix those inequalities but rather reinforced them and even generated new ones. Together with development, the creation of Sugarland exposed the sharp inequalities, especially between the lowlands and highlands, where, until the late 1980s was concentrated the bulk of the population in Albania. Maliq became a coveted destination for all the surrounding uplands and the system of “pashaportizimi,” established in the second half of the 1950s inhibited the free movement of people within the country. The communist regime’s solution was a measure that attempted to enforce on society specific choices of the state and discourage any response of the society to the collateral effect produced by state policies and the alternative the Tirana authorities followed.

In Maliq we can explore and shed light at a microscale on global processes that were not limited neither to Albania nor to the Balkans alone. In this periphery of Albania, we can see the implementation of the 20th century’s historical trends, especially the simultaneous engineering of nature and society. The ideological divisions wane when we scrutinize the processes that aimed at taming the environment and exploiting it in new forms that pertain to industrialization. In this sense, exploring the technology transfer and connectivity to the world, even in communist Albania, what we discover is that even Maliq, this periphery of a periphery was tightly tied to broad networks that saw the movement of ideas and practices across vast spaces. Thus, in Maliq, besides the factory and its machinery, the Soviets brought Jazz and Foxtrot. New ways of life made their way among villagers now newly minted into workers, technocrats, and urbanites. Polish, Romanian, Yugoslav, and even American technology was used in Maliq and its specialists traveled in many countries to bring to Albania the necessary know-how to make the Sugarland more productive and their industry more profitable.

Hence, Sugarland exposes a new painting of communist Albania that defies the stereotypes that have been circulating about the country. Besides, the story of Sugarland tells another story of the Balkans. This is not the story of the homogenizing nationalism and the violence used to undo the multicultural social fabric and cultural life of the Ottoman era. This story of nation-states that were meant to be modernizing platforms is not necessarily a story of extreme violence against the “Other.” While nationalism has been a central driving force, which has generated a series of unfortunate events and processes in the Balkans, we should not understand it only through the lens of ethnic cultural policy, abuse of minorities, or even genocide. In the Balkans and across Eastern Europe – and for that matter in the Global South – nationalism has also been a project of development. Development, progress, or modernization are not processes that take place in a vacuum. Void was not an option, especially for not developed countries, including communist Albania, despite Hoxha’s willingness to seclude the country as much as possible from the ideological influences coming from outside. The need to develop pushes nationalist modernizers to connect to the broader in new ways that aim to preserve the local without submerging it into the ocean of the general. This is not an apologetic effort to nationalism but rather an attempt to broaden the horizon of our analysis. Indeed, microhistory shows ways of connecting and drawing broader parallels in a macroscale that show that the Balkans is not merely a space of violent nationalism – although it has many times been – but also a locus where we can explore and understand historical processes that have marked the 20th century in both global north and south.

In this regard, microhistory helps us to overcome the trap of discursive analysis. It shows the incoherencies between what is said and what is done. If we follow, for example, the dominant discourse in communist Albania, the country emerges as something out of this world. However, by placing the lens in one single locality and exploring the actions and the practices, another historical landscape opens up, which helps us to better grasp the complex history of Albania, the Balkans, and for that matter of the 20th century. Regardless of the titanic ideological clashes, which created the impression of antagonistic systems that were diametrically different and opposed to each other, there were instead many threads that pointed to many shared similarities that transgressed the divides created by the secular religions of the last century and many essentializations through which regions have been depicted.